|

|

| GET A QUOTE: | ||||

|

| ||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

By Paul Davidson, USA TODAY

The nation is turning to alternative

energy as

never before amid concerns about global warming and runaway

fossil-fuel

prices.

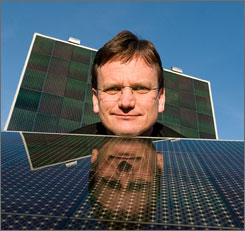

Wind and solar power, for example, each grew 45% last year, while the U.S. consumed 633,000 barrels of ethanol a day in June, up 43% from a year earlier. But alternative energy has not broken into the mainstream because of myriad roadblocks. Solar energy, for example, is expensive. Wind power is available only when the wind blows. But hundreds of companies are working to overcome the obstacles. Through June, venture capital investments in alternative energy companies this year totaled $980 million, up 92% from a year earlier, says Dow Jones VentureSource. Here are four technologies that show promise: Thin-film solar panels: Printing process cuts down on the cost of silicon, a key material Here's one way to bring down the price of solar energy: make churning out solar panels as easy as printing a newspaper. That's precisely what start-up Nanosolar has done. The company says it's poised to be the first among dozens of manufacturers to make solar competitive in price with conventional electricity. While solar-system costs have fallen, they're still about 20 cents to 30 cents per kilowatt hour, or more than twice the price of electricity from your local utility. That's largely because traditional solar-system makers use expensive silicon as a semiconductor to generate electricity from sunlight. Thin-filmmakers have pushed down costs by using a tiny fraction of the semiconductor. But most still employ a slow and expensive condensation method to attach the semiconductor onto a base. Yet with production volumes rising, solar energy generally is expected to be competitive with grid electricity in 2010 or after. Nanosolar, a Northern California company, says it can achieve that next year because of its printing process. It embeds tiny semiconductor particles in ink, then coats a layer of it onto mile-long rolls of aluminum foil, which is later cut into solar panels. The company says it can turn out panels at a rate of 100 feet a minute, 20 times faster than typical thin-filmmakers at a tenth of the cost. "It's all about higher throughput," to more cost-efficiently leverage fixed labor and equipment costs, Nanosolar CEO Martin Roscheisen says. In December, Nanosolar opened a factory in San Jose that's capable of pumping out 430 megawatts of solar capacity a year, nearly the size of an average coal-fired power plant. It plans to produce huge solar panels for cities and other utility-scale users this year and target businesses and homes next year. Consultant Paul Maycock of Photovoltaic Energy Systems says Nanosolar's systems "could be one of the more exciting products" in solar energy's history. But he says the company has not delivered the production volumes it promised a few years ago. Roscheisen would not discuss its output, noting Nanosolar is private. E-Coal: No greenhouse gas in coal substitute Imagine an electricity source that kind of looks like coal and packs all of coal's energy punch but is cheaper and produces no greenhouse gas emissions. That's what Seattle-based NewEarth Renewable Energy says it developed with E-Coal. It's biomass made from plants or other organic waste and heated to boost its energy content. "We can produce (clean) fuels that are pound-for-pound replacements for coal," NewEarth CEO Ahava Amen says. In 2004, after making a small fortune in cosmetics, Amen and some former associates reunited to tackle global warming. They hunted for a substitute for coal, the biggest greenhouse gas producer. Biomass emits carbon dioxide when burned but absorbs the same amount in its lifetime. Yet it yields a third to half of coal's energy, raising fuel costs and limiting the size of current biomass power plants. NewEarth boosts its energy content by placing the biomass in an oxygen-deprived chamber and heating it to 250 degrees. The resulting solid is condensed, and unwanted gases and moisture are removed. The heating process was invented decades ago, but Amen says NewEarth has made it cost-efficient. It's using as its feedstock a fast-growing plant, Nile reed. Because the energy value equals coal's, he says, there's no need to spend millions to upgrade plant boilers. Plus, he says, E-Coal costs 5% to 40% less than regular coal. Initially, a utility likely would blend a small amount of E-Coal with its coal. But Amen says a plant's entire fuel stock can be replaced. He says he's negotiating with dozens of utilities. Larry Joseph, former U.S. Energy Department official and investor in the company, says utilities are very cautious and want clear evidence they're not going to harm their equipment. Algenol: Company uses algae to make ethanol more eco-friendly Corn-based ethanol is getting slammed for straining the world's food supply and contributing to global warming by encouraging the plowing of grasslands. Cellulosic ethanol, a more eco-friendly version derived from switch grass or wood chips, is several years away. Maryland-based Algenol says it can solve the problems by making ethanol from algae, starting next year. The start-up recently agreed to license its technology to BioFields, which plans to build an $850 million saltwater algae farm in Mexico's Sonoran Desert and churn out 100 million gallons of ethanol the first year. It will sell the gasoline substitute to Mexico's state-run oil monopoly. A handful of companies are working on turning the abundant marine organism into biodiesel. That requires growing algae and killing them to extract their oil, a time-consuming and expensive process. Algenol adds enzymes to the organisms to enhance their normally limited ability to convert sugar into ethanol, a waste product. To maximize ethanol production, the algae are placed in regions with abundant sunlight and grown in 50-foot long tubes filled with seawater. Ethanol is captured as a gas in the bottle and condensed to a liquid. Since algae aren't destroyed, the same ones keep yielding ethanol, holding down costs. Algenol CEO Paul Woods says production costs are half those of corn-based ethanol, and the fuel will wholesale for $1 less than gasoline. His goal: Woods wants to build 20 plants in sunny areas such as Texas and Florida to generate 20 billion gallons of ethanol by 2020. "We don't have any limitations, because we're not competing with the food supply," Woods says. Philip Pienkos, of the National Renewable Energy Laboratory, says Algenol's goal is "definitely doable." But he says there will still be a need for fuels with higher energy content than ethanol. Compressed air: Facilities put stored air to work when wind dies Wind farms are sprouting across the country as wind energy costs become competitive with those of coal-fired power plants. But there's a rub: no wind, no electricity. Batteries can store electricity generated by wind for use on a day when the wind doesn't blow. But they're expensive. PSEG Global, a sister company of a New Jersey utility, says it has the answer. It recently teamed with energy storage pioneer Michael Nakhamkin to market compressed-air technology. Here's how it works: During off-peak hours, wind turbines compress air that's stored in underground caverns or in more expensive above-ground tanks. The air is released at peak periods to run turbines and generate power when gusts flag. The nation's only compressed-air generator was built in Alabama in 1991. PSEG says it has improved on the technology and hopes to deploy it with power providers. PSEG says its advanced system can transform the industry. It's about half the price of batteries, partly because it uses off-the-shelf power-industry parts rather than customized compressed-air gear. The technology is more than 25% cheaper than current systems, says Stephen Byrd, president of PSEG Energy Holdings. Also, it can generate electricity in five minutes, vs. current systems that take 20 minutes. That's vital if the wind suddenly stops blowing. "It really is likely to further enable the growth of renewable" energy, Byrd says. While the system is largely designed to supplement intermittent wind or solar power, it can be used to stockpile cheap electricity at night and use it midday when the grid is strained. Energy consultant Stow Walker says it sounds promising, but finding suitable underground storage can be challenging.

Guidelines: You

share in

the USA TODAY community, so please keep your comments smart and

civil.

Don't attack other readers personally, and keep your language

decent. Use

the "Report Abuse" button to make a difference. Read

more.

| |||||||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||

Yahoo! Buzz Digg Newsvine Reddit FacebookWhat's this?